Inflation, Supply & Demand, and Eggs: Part III

In Part I, we began our journey by examining the sticker price of eggs—the price we see on grocery store shelves—and then adjusted and benchmarked it against the Grocery Price Index. This allowed us to contextualize egg prices within broader trends in grocery inflation.

From this analysis, a surprising insight emerged: eggs, on the whole, have been more resistant to inflationary pressures than other grocery items. However, we also identified four distinct occasions when the indexed price of eggs surpassed the overall Grocery Price Index, signaling moments where the market for eggs was thrown out of equilibrium.

In Part II, we examined broader events surrounding these disruptions in detail, exploring the specific events and forces—like avian flu outbreaks, supply chain challenges, and seasonal demand—that drove these spikes. These moments gave us valuable clues about what happens when a market is pushed beyond its limits.

Now, in Part III, we’ll begin to explain market equilibrium from the supply-side. Let's get cracking (yes, I will continue using that pun).

Understanding Supply Chains

Before we get into the stats, it's important to level set on what a supply chain is. To boil it down to one sentence: A supply chain is the system of people, processes, and resources involved in producing and delivering a product or service, from raw materials to the final customer.

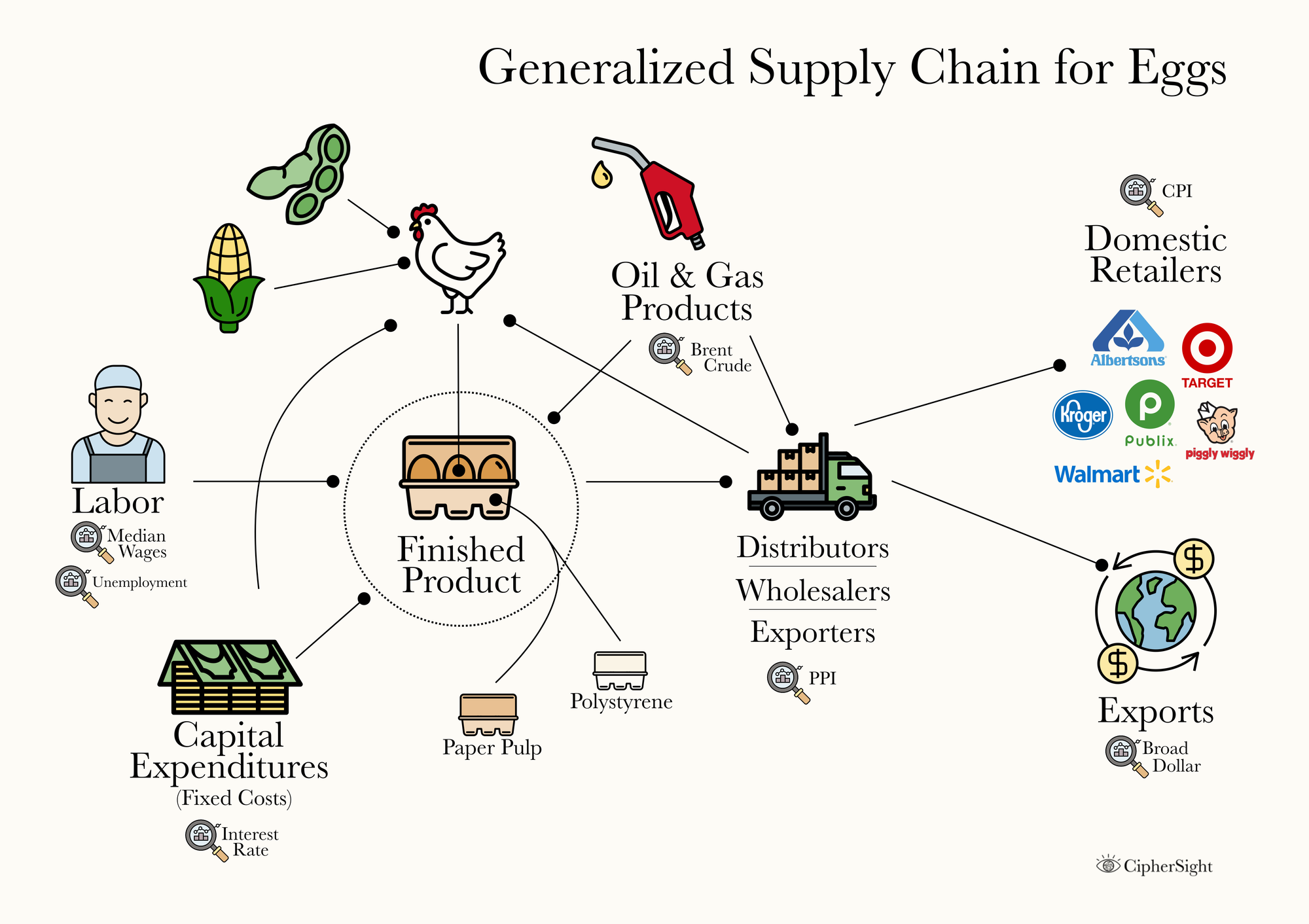

To be clear, I'm sure that there are people out there who've dedicated their whole careers to understanding the supply chain behind eggs, but I am not one of them—though if there are any of you out there and want to connect, please reach out! This is important to keep in mind because I will attempt to sketch out a generalized version of what I believe the supply chain looks like as an Economic Naturalist and a final consumer of eggs, not an expert. For the purposes of this analysis, the supply chain for eggs looks like this:

Notes on the Diagram:

- Packaging: At the supermarket, I’ve noticed a variety of packaging options for eggs, but the most common materials are paper pulp and polystyrene. I’m not certain of the exact market share between the two, so for now, I’ll treat them equally in this analysis.

- Distributors, Wholesalers, and Exporters: I’ve grouped distributors, wholesalers, and exporters together due to the likely variation in the degree of vertical integration within the egg production industry. For instance, large retailers like Walmart and smaller grocers like Piggly Wiggly (real ones know you “Save Big at the Pig”) may have different levels of supply chain consolidation. This nuance is currently beyond the scope of this analysis. For this step in the supply chain, I’ll rely on the Producer Price Index (PPI) for eggs. Formerly known as the Wholesale Price Index, the PPI reflects the prices that retailers pay for eggs before applying their markup and selling them to consumers.

- Capital Expenditures: Capital Expenditures include investments in machines, equipment, and infrastructure like barns. A simple way to think about capital is to picture someone digging a hole: the person is the labor, the shovel is the capital, and the hole is the finished product. Generally, large capital expenditures are financed, meaning borrowing costs (e.g., the Federal Funds Rate) directly influence the level of capital investment. Increased investment could lead to more housing for hens, boosting supply and lowering prices. Alternatively, it could involve machinery upgrades to improve operational efficiency, potentially reducing variable costs and passing savings on to consumers.

- Replenishing Livestock: Initially, I searched the FRED database for data on the cost of chicken livestock, but I realized that egg producers likely replenish their flocks using fertilized eggs from their own supply rather than purchasing new stock. The exception would be after significant disruptions like mass culling during a Bird Flu outbreak—which they would buy from wholesalers. While I’m not entirely certain this assumption is correct, I will proceed with it for the purpose of this analysis.

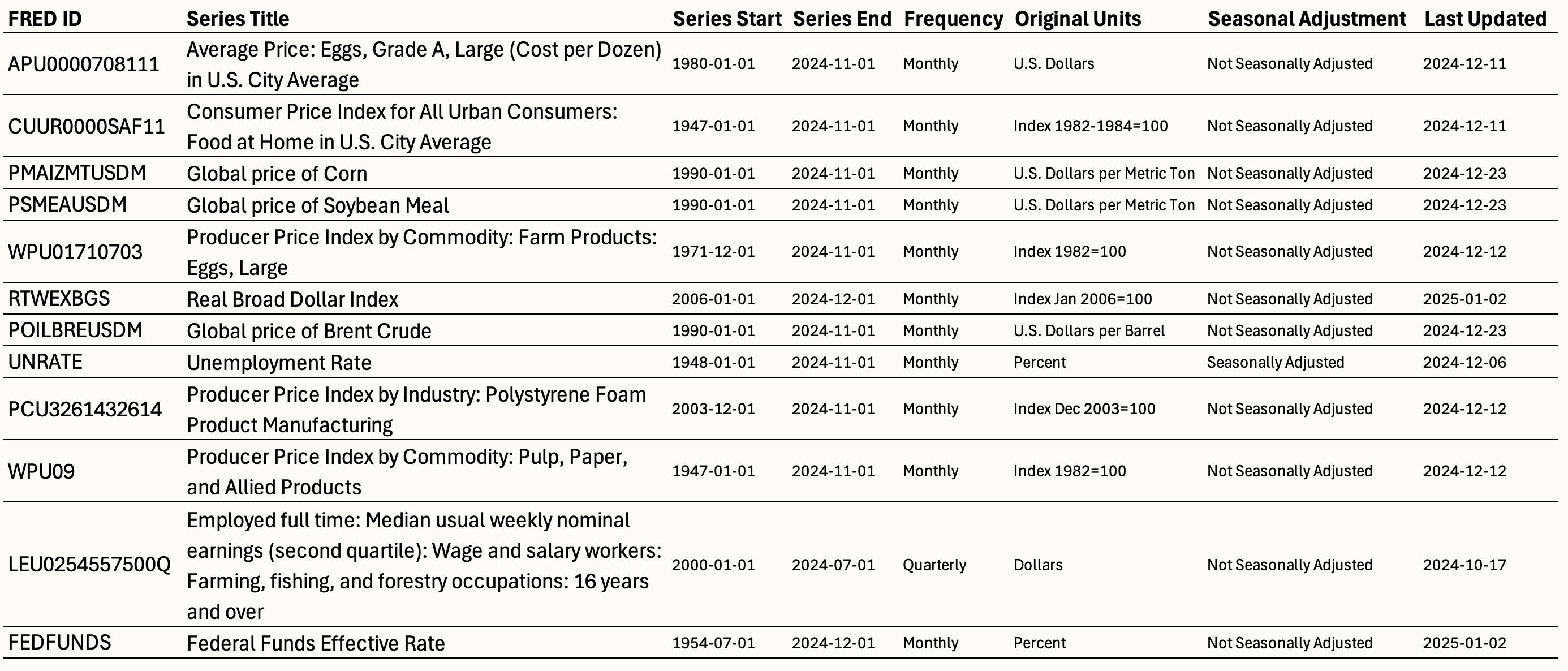

Data Dictionary

As this analysis has progressed, I've been hyperlinking results to the FRED page so that you can access the data I'm referencing directly. In Part IV, we will begin our statistical analysis of the Generalized Supply Chain outlined above. For ease of reference, the data I'll be working with is as follows:

Notes on the Data:

- The Unemployment Rate is seasonally adjusted while the others data series are not. This is intentional because the unemployment rate has a predictable quarterly / semi-yearly pattern that is largely persistent across the entire time series. See what that looks like here. For this analysis, we're interested in the broader unemployment trend and leaving aside the predictable, inherent fluctuations.

- To look at the price of crude oil, I'm using the Global price of Brent Crude. Brent Crude is broadly defined as "any or all of the components of the Brent Complex, a physically and finacially traded oil market based around the North Sea of Northwest Europe." Even though U.S. agricultural producers are not likely buying crude oil from the North Sea directly, Brent is used to "set the price of two-thirds of the world's internationally traded crude oil supplies," and is therefore a good proxy for the overall cost of petroleum products. A more clearly defined supply chain for these petroleum products is outside the scope of this analytics series.

- The Broad Dollar, Trade Weighted Index is only available from January, 2006 to present. Rather than trying to piece together other time series to get a longer history, but wanting to ensure that the proper relations are maintained, I've re-indexed all of the time series to where Jan 2006 = 100. For the prior months, the Broad Dollar index will be classified as NULL. I saw a meme in the past that was spot on in describing the best way to differentiate NULL values vs Zero values is to think about not having any toliet paper: Zero toliet paper means there's no toliet paper on the roll, Null means there's no roll to begin with. This becomes important in statistics and data analysis because placing zeros where there should be NULL values can unintentionally distort the final results.

- The Median Farm Wage input is reported quarterly rather than monthly (like the other time series). To account for this, I imputed the missing data using the Last observation carried forward method. For example, the value for Q1 2024 would be applied to January, February, and March rather than January alone.

Conclusion to Part III

In this part of the analysis, I outlined a generalized supply chain for eggs, breaking down its key components to better understand the factors influencing egg production, pricing, and distribution. By mapping out this supply chain, we can see how interconnected elements—like feed costs, labor, capital expenditures, and packaging—work together to deliver a finished product to consumers.

Additionally, I established a data dictionary to organize the key metrics and indicators that will drive this analysis. These include time series data from FRED for inputs like feed prices, energy costs, labor rates, and Producer Price Indexes, along with other relevant economic indicators.

With this framework in place, we are now equipped to dive deeper into the data to identify patterns, analyze disruptions, and explore how shifts in any part of the supply chain ripple across the system. In Part IV, I’ll begin to explore this data model in more detail and introducing fundamental statistical methods that can be used to help further understand and describe dynamics in the egg supply chain.

Stay tuned as we transform this foundation into insights, uncovering how the links in the supply chain shape the journey from farm to table!