Inflation, Supply & Demand, and Eggs: Part II

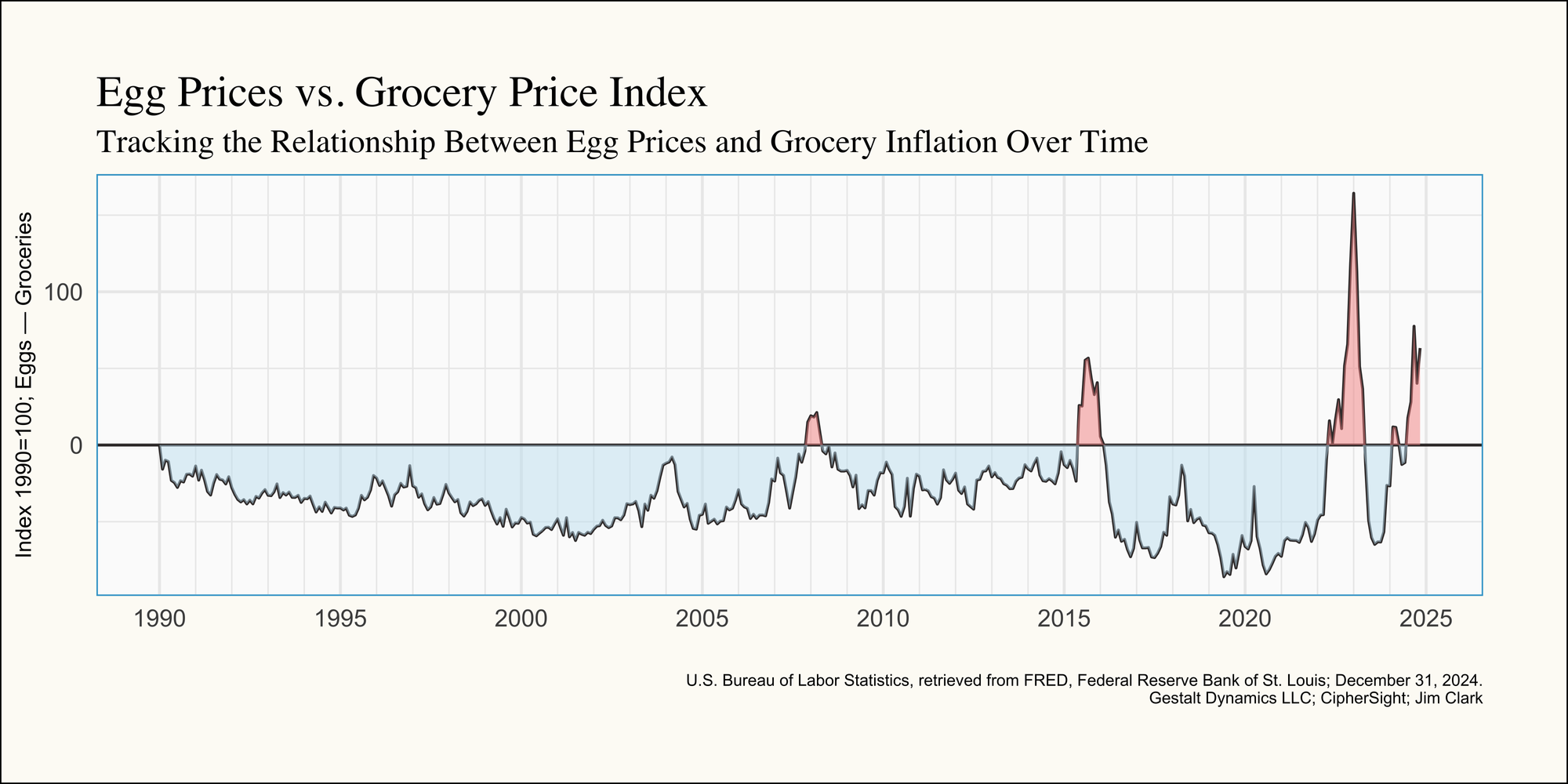

In the previous post, we took the raw data from the FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data) for both the nominal cost (sticker price) of a dozen eggs since 1990 and the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for Food at Home over the same period of time which I've taken the liberty of calling the Grocery Price Index. The main reason for doing this is that it allows us to see the cost of eggs adjusted for inflation in overall grocery prices as well see how the cost of eggs has increased relative to the other components of the Grocery Price Index. I ended the previous post with a chart that overlays the indexed price of eggs minus the Grocery Price Index (referenced below). If you are unsure of how we've gotten to this point or need additional background, I encourage you to read the previous post and/or email at Jim@gestaltdynamics.com to let me know how I can provide further clarification in the future. Now with the preamble out of the way, on to Part II!

Looking at the chart above, the first thing that stands out is the four distinct instances where the price of eggs outpaced the overall Grocery Price Index. These spikes suggest potential supply shocks during those periods, which should be relatively straightforward to investigate. The second notable observation is how resilient the price of eggs has been over time, consistently remaining below the overall Grocery Price Index except during those isolated events. This will be a bit harder to explain, but I will lay out some potential hypotheses for why this is in Part III. As to the anomalies, let's see if we can better understand events during those periods that may have led to increased prices:

Early 2008

- Rising Feed Costs: in 2008, feed costs (corn and soybean meal) were significantly impacted by a surge in global commodity prices. Corn prices in particular skyrocketed due to the increasing use of corn for ethanol production, driven by U.S. government mandates to expand biofuel usage.

- Rising Oil Prices (Transportation Costs): High oil prices in 2007 and 2008 increased transportation costs, futher adding to the cost of production.

- Increased Demand for Exports: Exchange rates favorable for exports (a lower number, or a "weaker dollar" in early 2008 made exports relatively cheaper), as measured by the Trade-Weighted U.S. Dollar Index. This growing global demand for eggs produced in the U.S. reduced the domestic supply and put upwards pressure on prices.

- Local Concerns about Avian Influenza (Bird Flu): Although not as prominent as in later years, localized outbreaks of Bird Flu in some areas around the world, particularly Indonesia and Egypt, raised concerns about supply constraints, indirectly contributing to higher prices as producers were possibly hedging against the costs associated with culling their flocks.

Mid-to-Late 2015: Bird Flu in the U.S.

- Bird Flu Outbreak: The virus spread rapidly, particularly affecting flocks in the Midwest, a major hub for egg production. Over 50 million birds were culled to contain the outbreak, including tens of millions of egg-laying hens, leading to $3.3B of livestock losses to the industry and a subsequent sharp drop in egg supply.

- Supply Shock: The sudden reduction in the number of egg-laying hens caused an immediate and substantial supply shortage.

- Increased Production Costs: Egg producers faced higher costs due to the need to cull infected birds, sanitize facilities, and rebuild their flocks. The time required to repopulate egg-laying hens (typically about 16-21 weeks to reach full production capacity) further prolonged the supply disruption.

- Gradual Recovery: Egg prices began to normalize by late 2015 and early 2016 as production recovered and new flocks of hens began laying eggs. However, the impact of the outbreak lingered, with some producers taking longer to rebuild operations.

- Possible Over-Correction: As seen in the chart at the top of the article, indexed egg prices dropped to levels lower than those observed pre-pandemic. This is likely due to producers over-populating their flocks, leading to an oversupply in the market. With excess inventory, producers were willing to sell at lower prices to clear the surplus.

2022 to Early 2023: The Perfect Storm

- Bird Flu Outbreak: Another severe outbreak of Bird Flu swept across the U.S. starting in early 2022. Though less severe than the 2015 outbreak (this time around 23 million birds were culled). All of the previously described effects from the 2015 pandemic were repeated: the supply shock, the increased production costs, and the gradual recovery.

- Rising Production Costs: Similar to early 2008, Corn prices remained elevated in 2022 along with soybean meal, both used as livestock feed. Additionally, this time period experienced a tighter labor market where the seasonally adjusted Unemployment Rate stayed at a low of between 3.4% to 4%, coming off of the ~15% high watermark in April 2020 (Response to COVID-19 pandemic). This low rate of unemployment implies that employers need to offer higher wages to entice workers to work for their firms.

- Seasonal and Psychological Factors: The holiday season is strongly associated with increased cooking and baking, leading to a predictable spike in egg demand. In the chart at the top of the article, the greatest divergence between indexed egg prices and the Grocery Price Index occurs during the holiday period of 2022. This heightened demand was likely exacerbated by widespread media coverage of egg shortages, which may have fueled panic buying and potentially enabled price gouging.

2024 to Present

At this point, restating why we find ourselves in the current situation from 2024 onward might feel redundant. Bird flu has made a strong resurgence, now spreading beyond chickens and turkeys to cows and even humans who work in close contact with infected animals. One potential response to these recurring bird flu pandemics could involve implementing stricter animal welfare standards (e.g., cage-free requirements), which would inevitably raise production costs and, in turn, retail prices.

Additionally, other supply chain disruptions—such as volatility in the markets for agricultural products used as feed (mainly corn and soybean meal), or increased costs associated with transportation, packaging, and storage—are likely contributing to rising production costs. These challenges, whether caused by labor strikes, logistical bottlenecks, or extreme weather events, are ultimately driving up the costs passed on to consumers.

Conclusion to Part II

Oftentimes, the best way to understand how a system works is to observe what happens when it breaks—either by fixing it or studying how it was restored. By examining the various spikes in egg prices relative to the Grocery Price Index and the events surrounding those disruptions, we gain valuable insights into the factors that can throw this system out of equilibrium.

If we understand what drives these disruptions, we can leverage that knowledge to create scenario-based predictions. Anticipating how specific factors—such as supply shocks, inflation, or policy changes—affect equilibrium allows us to make more informed decisions and better prepare for future volatility.

In Part III, I will explore this state of equilibrium in greater detail, using insights from the spikes we've examined to better understand the underlying correlations and associations that keep the system stable and what pushes them to the brink.