Inflation, Supply & Demand, and Eggs: Part I

Imagine this: Last year, you could walk into your local grocery store and grab a dozen eggs for less than $2. Today, that same carton might set you back $5 or more. If you’ve stood in the dairy aisle recently and wondered what’s going on, you’re not alone. Eggs—a staple of breakfast tables, bakeries, and countless recipes—have become a symbol of something much larger: inflation. This boogyman has been ever-present over the past few months and egg prices in particular have played an outsized role in shaping narratives that prices are getting out of control and we need someone to step in and reign everything back in.

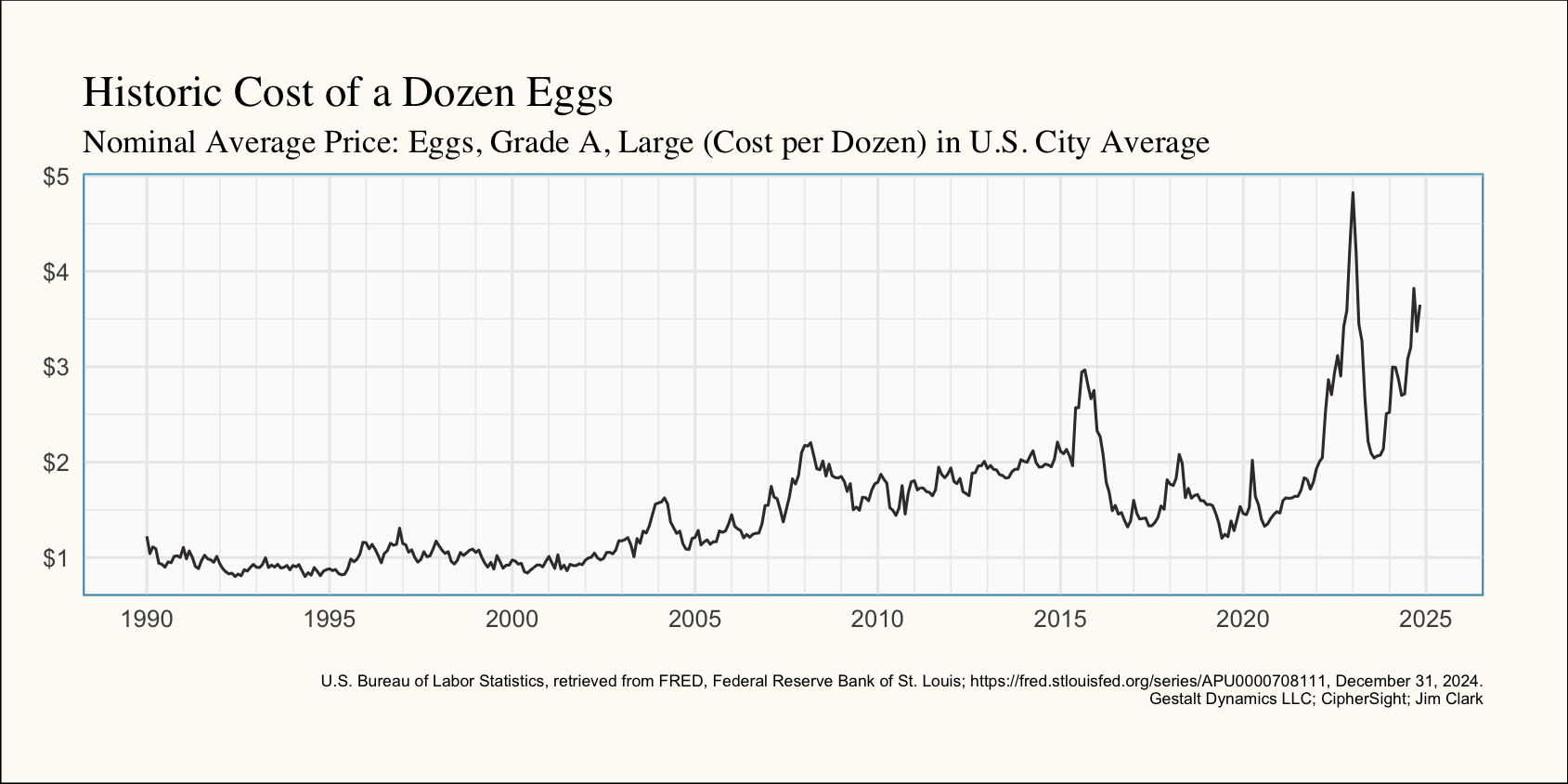

However, egg prices don’t just fluctuate at random. They're a perfect case study in how supply and demand, coupled with larger economic forces, shape what we pay at the checkout counter. Let’s crack open the story of eggs to understand not just why breakfast is pricier but how the mechanics of inflation impact everything we buy. But first, lets look at the data (FRED series):

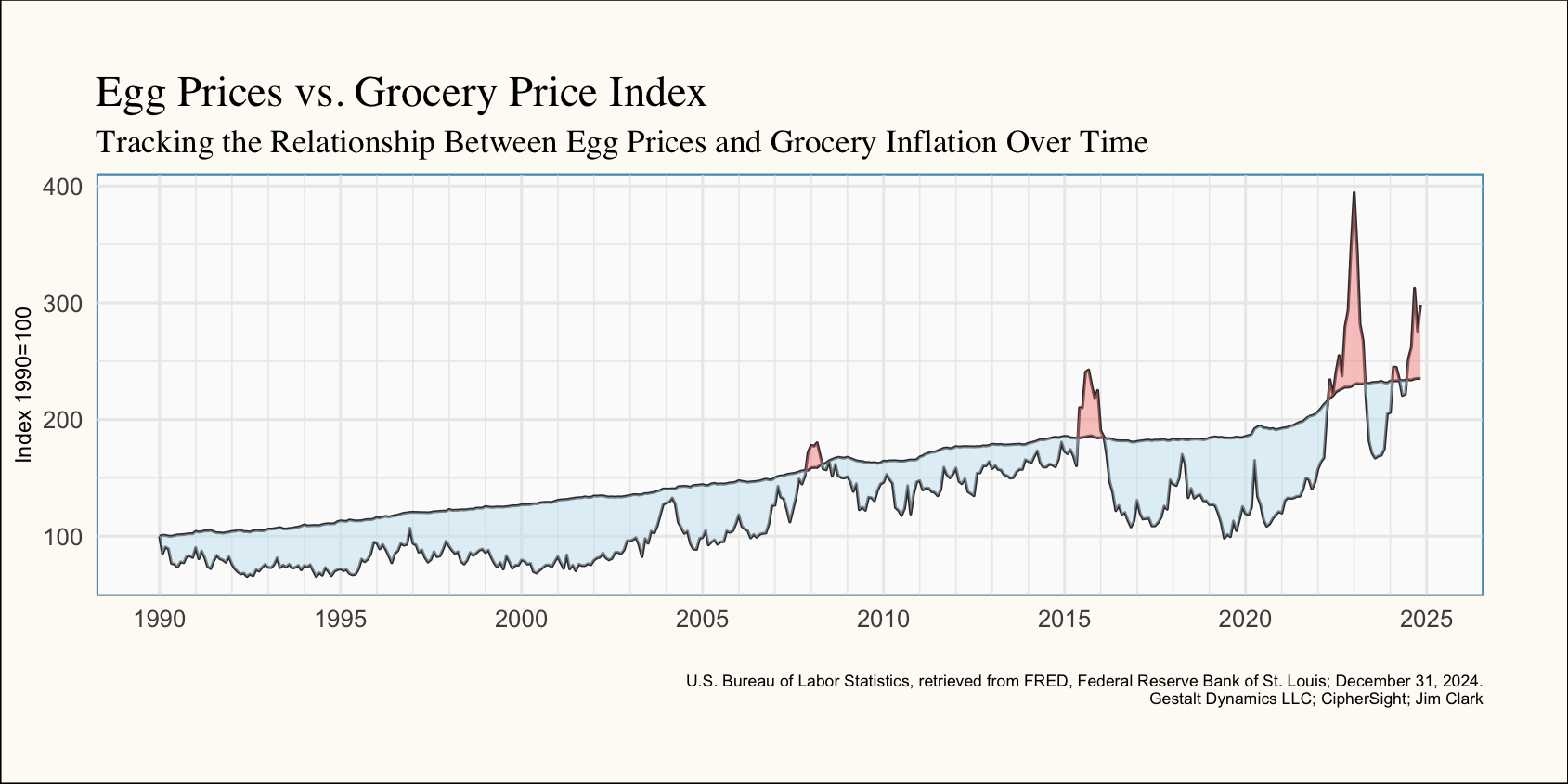

Without additional context, we can clearly observe that the nominal price (i.e., sticker price) of eggs remained stable, around $1 per dozen, from 1990 to about 2004. Starting then, prices began a steady climb, reaching approximately $2 per dozen by mid-2015, followed by a sharp jump to $3 per dozen. What ensued was a period of significant volatility, peaking at roughly $4.75 per dozen in January 2023, before quickly adjusting back to $2 per dozen by mid-2023. Since then, prices have been on a steady upward trajectory.

Before diving deeper, I’ll preface this analysis by acknowledging that markets are complex, multifaceted, and often unpredictable. However, by examining the price of eggs over time, we can gain valuable insights into the nature of inflation and how it is sometimes conflated with broader disruptions in the supply and demand equilibrium. First, let’s address inflation.

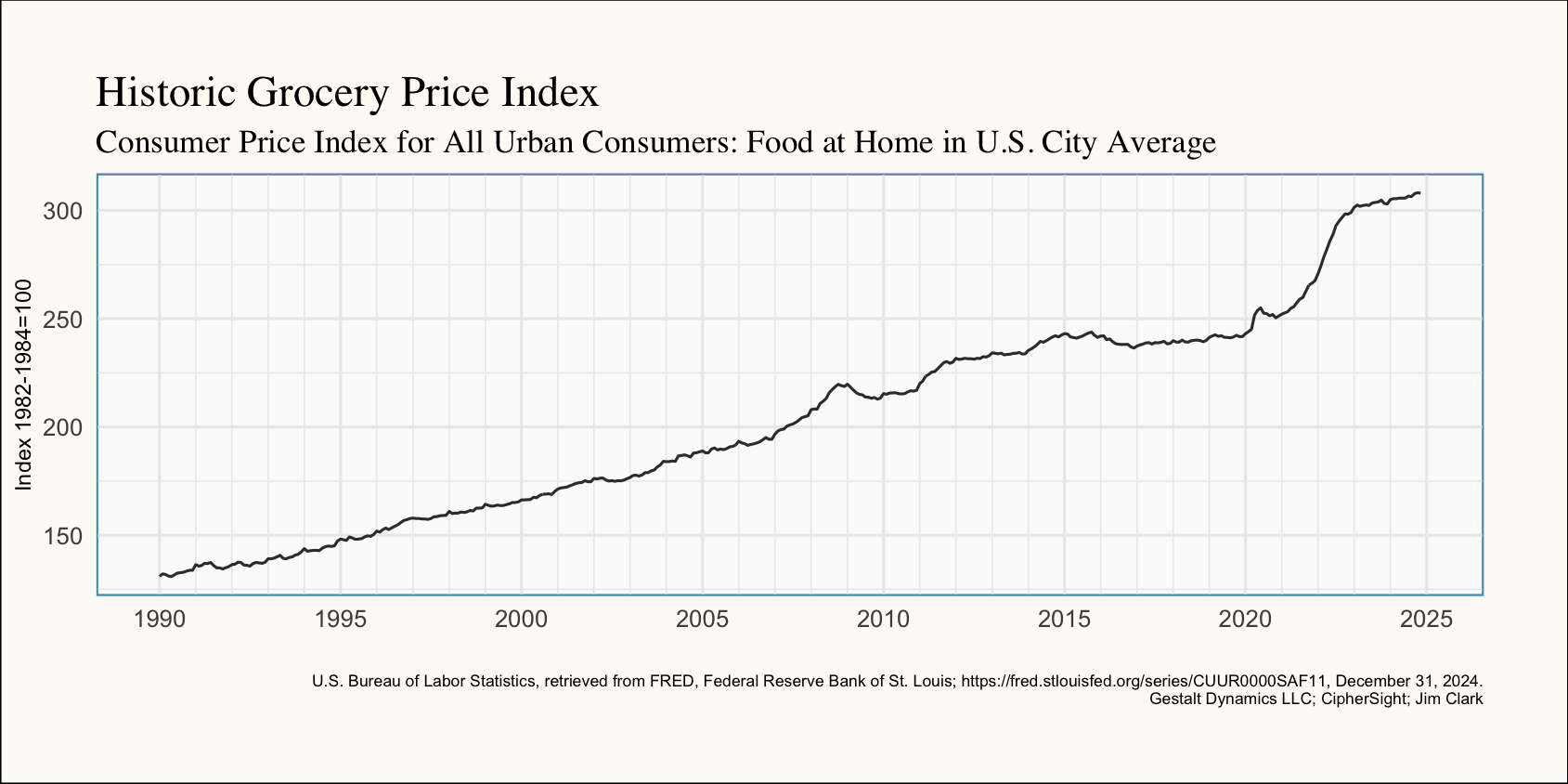

Much has been written—both in print and online—about what inflation is and its role in economic growth. While I intend to share a more detailed perspective in a future post, for the purpose of analyzing egg prices, let’s define inflation simply: it exists, and the most effective way to measure it is by examining changes in the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

The CPI is best understood as the average American’s metaphorical credit card bill—an aggregate tally of typical consumer expenditures, ranging from housing and transportation to education and, yes, eggs. It’s important to note that the composition of this “basket of goods” changes over time. For example, modern CPI figures include cell phone bills, a category absent from CPI calculations in the 1970s.

Food and beverages account for roughly 15% of the total CPI. For this analysis, we’ll focus on comparing the cost of eggs to the average cost of food at home and will be calling this the Grocery Price Index. To ensure consistency, we’ll reference the monthly, non-seasonally adjusted time series from the Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) series.

Before diving into the trend line, let’s first talk about the units. Indices, which aggregate a variety of disparate items, are typically benchmarked to a value of 100 at a specific point in time—this point can be either meaningful or arbitrary. For this grocery price index, a value of 100 corresponds to the typical cost of buying food for home consumption between 1982 and 1984. Since the index has surpassed 300 as of 2023, this effectively means that, on average, grocery prices are now three times what they were in the early 1980s.

With that context in mind, let’s interpret the trend. We observe a gradual increase in prices starting in the 1990s, followed by a plateau beginning around 2015. There’s a noticeable bump in early 2020, likely driven by the disruptions caused by COVID-19, and prices have since soared. Interestingly, when viewed over a longer timescale, this recent sharp rise appears to bring grocery prices back in line with the gradual upward trend that was consistently present from 1990 to 2015.

Now that we have our two primary data sources—the price of eggs over time and the overall indexed price of groceries over time—we can begin to analyze the extent to which the recent surge in egg prices is attributable to general inflation, price gouging, or other disruptions in the supply and demand equilibrium.

Though our data is roughly in the same structure (monthly, non-seasonally adjusted, from 1990-2025), they are still in very different units (dollars, and the generalized grocery index). To better make an apples-to-apples comparison, we'll re-index both time-series so that January, 1990 = 100. Overlaying the two series, we get the following:

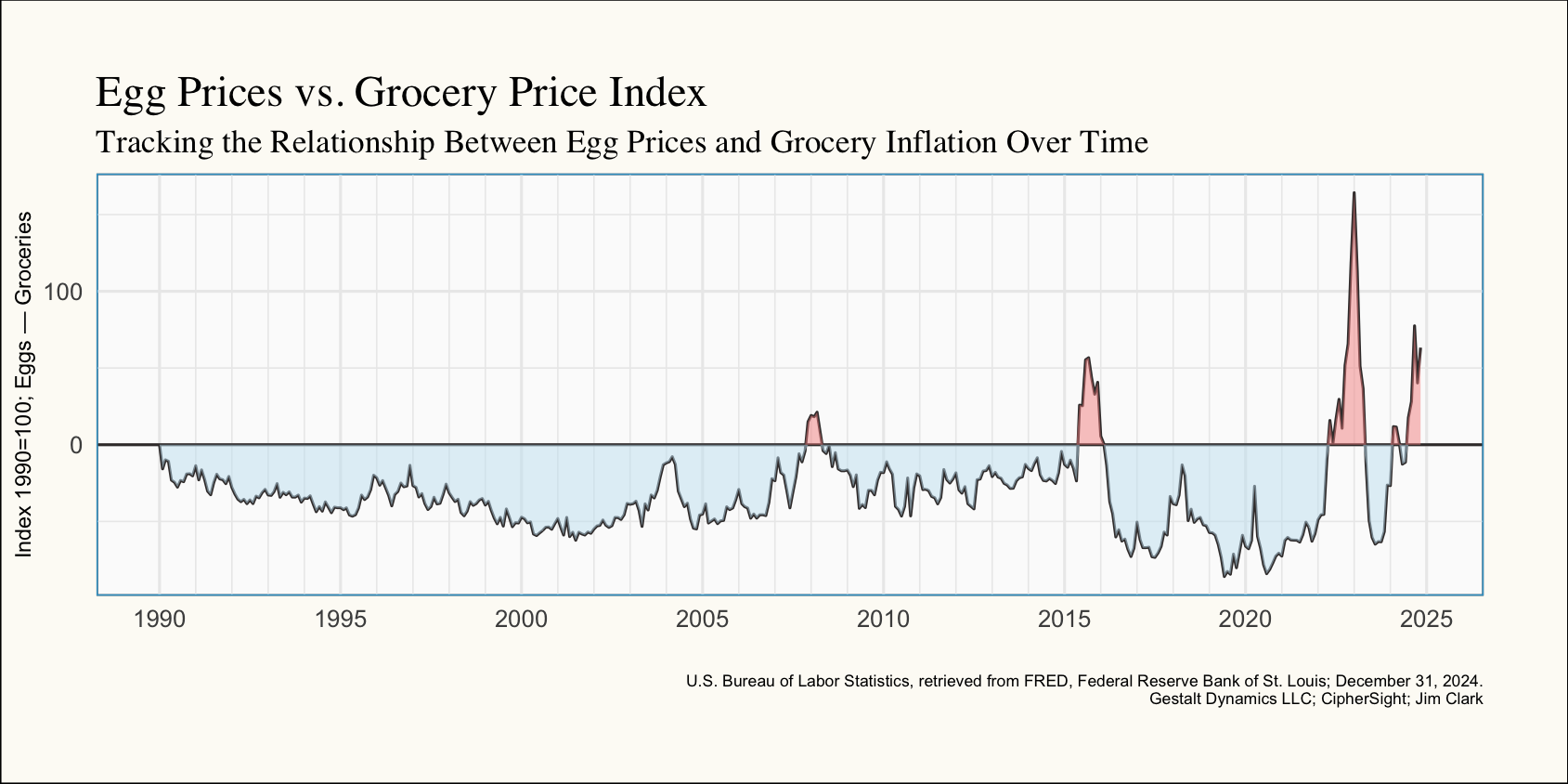

While the preceding chart helps illustrate the relationship between egg prices and overall grocery inflation, it does not provide a straightforward comparison of how much egg prices have deviated from the general trend. To address this, the next chart shifts the perspective to focus on the difference between egg prices and the Consumer Price Index (CPI), offering a clearer view of how egg prices have moved relative to overall grocery inflation over time:

Conclusion to Part I:

In this first part, we’ve established the historical context of egg prices, explored their relationship with overall grocery inflation, and identified the broader economic forces at play, such as supply and demand dynamics and inflation. By re-indexing the data, we’ve created a foundation for more meaningful comparisons, enabling us to better understand how egg prices have diverged from the general trend.

However, the story doesn’t end here. While inflation plays a role, it’s not the sole explanation for the recent spikes in egg prices. In the next part, we’ll dive deeper into the specific disruptions in the supply chain, market dynamics, and external factors—like avian flu outbreaks—that may have contributed to these fluctuations. Through this lens, we’ll gain a clearer picture of the forces driving the cost of this everyday staple.

Stay tuned as we crack open the next layer of this economic puzzle!